OPINION

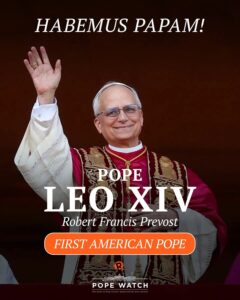

What is in the race or name? When it comes to a pope – everything. The white smoke from the Sistine Chapel on Thursday told the world that a new pope to succeed Francis had been elected – and for the first time the pontiff is from the US.

In his words from the balcony of St Peter’s Basilica, the newly elected Pope, Leo XIV told the 40,000-strong crowd and the millions of Catholics watching around the world that: “We must be a church that builds bridges.”

But the new Pope only has to look to his native country of the US to see how damaging division can be – yet he will know how damaging division in the church is too.

In fact, the new Pope need not to overlook the process through which he ascended to his current position. Out of 266 past leaders of the Catholic Church, none should, and indeed has been an African, and for the conclave, it is okay.

The absence of a Black pope in the history of the Catholic Church is the result of historical, political, and institutional factors rather than theological exclusion.

Well, at this point, it is necessary for African Catholics to ponder and if need be, stop taking some things for granted.

For instance, since the olden days of the biblical Noah, black color which strongly represents Africans’ dark skin, has been taken and used to mean evil or satanic as opposed to the white, which in most cases represents the white skin of the Bazungu, used to mean good, or holiness. This is already discriminative!

You don’t actually need to wonder why the black smoke during the election of the Pope has to mean negative (Pope not voted), whereas the white smoke means positive (indicating that the new Pope has been elected).

Much as Africa currently have approximately 281 million baptized Catholics which represents about 20% of the world’s total Catholic population, still, Africa means so less or even nothing when it comes to electing the Pope. You might say that we participate, but that is not enough when none of the black Catholics cannot be trusted with papacy.

Even though, the Catholic Church in Africa is experiencing significant growth, with the number of Catholics increasing from 272 million in 2022 to 281 million in 2023. The Democratic Republic of Congo has the largest number of baptized Catholics in Africa, followed by Nigeria. But when will this black continent be given a chance to lead the Catholic Church?

The history of the Roman Catholic Church spans over two millennia, yet no Black pope has ever been elected. This absence raises questions about racial representation, historical influences, and the political nature of papal elections. While three early popes—Saints Victor I, Miltiades, and Gelasius I—were of North African origin, no pope of sub-Saharan African descent has ever held the papacy. Understanding why this is the case requires an exploration of historical, geographical, cultural, and institutional factors that have shaped the Church’s leadership.

Christianity has deep roots in Africa, particularly in Egypt and North Africa, where early theological developments flourished. Saint Victor I (c. 189–199), Saint Miltiades (311–314), and Saint Gelasius I (492–496) were all African by birth or descent.

However, these figures lived in a time when Roman Africa was an integral part of the Roman Empire, and their ethnicity was not necessarily viewed through a modern racial lens.

Following the decline of the Roman Empire, the influence of North African Christians diminished due to the rise of Islam in the 7th century. The weakening of the African Christian presence contributed to the absence of African candidates for the papacy in later centuries.

By the Middle Ages, the leadership of the Catholic Church had become heavily Eurocentric. The papacy became closely linked with European monarchies, and the College of Cardinals, responsible for electing the pope, was overwhelmingly composed of European clerics. This structure made it difficult for non-Europeans, including Africans, to ascend to the highest ranks of the Church.

The Catholic Church also developed as a political entity with strong ties to European rulers. Popes were often chosen for their ability to navigate European power struggles rather than for purely theological reasons. As European empires expanded through colonization, the Church’s hierarchy remained closely tied to European interests, reinforcing a system that marginalized non-Europeans.

The era of European colonization, beginning in the 15th century, played a significant role in shaping the demographics of the Catholic Church’s leadership. While missionaries spread Catholicism to Africa, they often established structures that kept native Africans subordinate to European clergy. African priests were rarely promoted to high-ranking positions, and the idea of an African pope was not seriously entertained in ecclesiastical circles.

Even as African nations gained independence in the 20th century, the effects of colonial-era hierarchies persisted. The leadership of the Church remained predominantly European, with African cardinals making up only a small fraction of the College of Cardinals. This limited their influence in papal elections and reduced the likelihood of an African pope being chosen.

In recent decades, the Catholic Church has seen significant growth in Africa. Today, Africa is home to some of the world’s fastest-growing Catholic populations, with millions of faithful and a growing number of clergies. African cardinals have been appointed to influential positions within the Vatican, reflecting the Church’s recognition of Africa’s importance.

Despite this progress, the number of African cardinals remains relatively small compared to their European counterparts. The papacy is often filled by individuals who have long-standing experience in Vatican administration, a path that has historically been less accessible to African clerics.

Additionally, there remains an implicit preference for European candidates based on tradition, familiarity, and geopolitical considerations. The cultural and institutional inertia of the Church has made it difficult for non-Europeans to break into the highest echelons of leadership.

The elevation of an African pope would be not only symbolic but also reflective of the church’s evolving global demographic footprint.

But even in a mostly conservative continent, the elevation of an African cardinal to the papal throne would be widely interpreted as a continuation of Francis’ track record of standing up for the poor and oppressed, migrants and civilians fleeing war.

Even if the next pope is not African, as the continent fast becomes a main population centre for the church, African Catholics will be expecting more “frequent visits” and speeches from their new leader.

The Catholic Church has inflicted unimaginable horrors on Africans, and the next pope must address the role the Catholic Church played in the transatlantic slave trade and the colonization of the continent.

By Ivan Tsebeni,

The Writer is a Ugandan Politician and Media Personality

Email: itsebeni@newvision.co.ug